Vol. 21, No. 13

- The past few years have seen concerns regarding antisemitism regularly expressed in Jewish circles.

- The United States campus community is considered by many to be a center of anti-Israel activity and antisemitic sentiment.

- The Jewish campus professional, whose life focus is the campus community, is uniquely positioned to assess the nature and extent of these activities.

- We report here on data gathered from campus professionals in 2015 and 2021 and analyze the trends and differences.

- The data suggest that while specific campuses may represent centers of antisemitic and anti-Israel activity, the broad generalization of “the campus” as a problem for Jewish students may be inaccurate.

- We also found that contrary to sentiment in the general Jewish American community, the assessment of campus professionals is that liberal and progressive groups represent the more significant source of antisemitic and anti-Israel sentiment on campuses than do more conservative groups, who are viewed as generally supportive.

Anecdotal and documented reports1 of a perceived rise in antisemitic incidents in the United States have been of concern to many in the Jewish community. In looking at the reports, it is common to see attribution of these incidents to “hate,” especially when stemming from nationalist or white supremacist sources. It is also often assumed that “education” is one way to curtail the perceived problem. Not all these assumptions, however, have been verified by databased studies.

For many years, the United States “campus” was considered by many a center of antisemitic and anti-Israel activity. Many Jewish organizations have devoted resources to combat this activity,2 and Jewish student leaders have written about the issue.3 Reports citing a “rise” in antisemitic campus incidents are common4 with a prevailing “conventional wisdom” that appears to assume a pervasive presence of such activity on most university campuses in the United States. Using a series of focus groups, conversations, and surveys with Jewish campus professionals, it appears that while these issues do, in fact, exist, the extent and intensity may vary from being a significant problem to a non-existent one, depending on the campus. Accordingly, generalizing the issue across “the campus” in general may not be accurate.

While overt physical acts that include attacks of destructive behavior are easy to identify and label as “antisemitic,” other activity is less recognizable. Especially when activity focuses on a human rights approach that accuses Israel of abuses, the line separating racist-based antisemitic activity from more acceptable political opposition in the form of anti-Israel behavior can become blurred and disappear. Indeed, while the widely accepted International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) working definition of antisemitism addresses this by generally including much anti-Zionist activity as antisemitic, an alternative definition, that of the “Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism,” specifically does not. IHRA has been accepted by the United States Department of State,5 while the Jerusalem Declaration has been endorsed by many individuals and representatives of non-government organizations (NGOs) who are generally identified as left-progressive on the ideological-political spectrum.6

Using the IHRA criteria, certain activities seen on campuses would be considered antisemitic. For example, activities that are seen on some campuses “denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination” or “targeting of the state of Israel, conceived as a Jewish collectivity,” would be specific examples of antisemitism.7

Using the IHRA working definition, there is little doubt that there is antisemitic activity on American college campuses. However, there may be a perceptual divide between the actual campus reality and the impression that many, especially those outside the campus community, have. For example, in a 2015 report by the Cohen Center at Brandeis University, there was substantiation of anti-Israel activity on campus, but only about 25% of students felt this to be a “major problem.” Even though many experienced exposures to antisemitic statements, actual antisemitic activity was almost exclusively verbal in nature.8 This was also found in a previous study9 by Trinity College researchers (National Demographic Survey of American Jewish College Students 2014). The ADL’s recent report10 seems to reinforce the notion that the overwhelming nature of antisemitic activity on campus in the United States is related to organized campus groups engaging in anti-Israel activity as opposed to actual “incidents” of antisemitism specifically directed toward Jewish students. The data seem to support the notion that Israel serves as the focus of antisemitic activity and that this activity, when experienced by Jewish students, is focused on verbal rather than any actual physical harassment. The actual amount and intensity of this activity, however, is often a matter of subjective reports by students, often relying on their personal perception rather than any objective criteria.

One other possible explanation may be the differing concepts of what “antisemitism” actually means to people. While the aforementioned IHRA definition is widely quoted, the “Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism” exists as a counter-definition. As opposed to the IHRA, the Jerusalem declaration allows broad exceptions for anti-Israel activity, specifically noting that these should not be considered examples of antisemitism. Included in these activities are “…opposing Zionism as a form of nationalism…” and stating clearly that: “It is not antisemitic to support arrangements that accord full equality to all inhabitants’ between the river and the sea,’ whether in two states, a binational state, unitary democratic state, federal state, or in whatever form.” The declaration also does not necessarily consider the BDS (Boycott, Divest, Sanctions) movement to be antisemitic.

For many, supporting BDS, opposing Zionism, or more specifically, opposing the recognition of the Jewish people as a distinct “nation” entitled to self-determination and calling for the elimination of the State of Israel (something that the slogan “from the river to the sea Palestine will be free” appears to promote11) is indeed antisemitic, something the Jerusalem declaration signatories do not agree with.

2015 Study: Jewish Professionals on Campus

Jewish professionals on campus have a unique perspective on the antisemitic and anti-Israel activity. As opposed to other Jewish activists, the campus is the life focus for these professionals. They experience the campus and its culture as members of the university community and not as outsiders relying on the reports (and interpretations) of others. An unpublished study conducted by the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs in 2015 surveyed Hillel directors on a number of issues related to antisemitic and anti-Israel activity on campus.12 It was found then that the perspective of these campus professionals showed that antisemitic and anti-Israel activity was a problem stemming from only a minority of students on their campus. Moreover, while very few of the campus professionals felt that antisemitism was an actual problem on their own campus, many were under the perception that “other” campuses did have a problem. They also did not report any actual physical attacks related to antisemitism, although the vaguer perception by students that verbally offensive remarks of an antisemitic nature were present was reported to some degree.

These findings contrast with the “conventional wisdom” regarding the level of antisemitism on campus and appear to support the less popular notion that while the average Jewish student may experience some verbally offensive antisemitic remarks on occasion, their general life on campus is not marked by the presence of significant antisemitism.

Current Study: Israeli Professionals on Campus

The Jewish Agency for Israel operates a program where emissaries are trained and assigned to various campuses in the United States.13 These emissaries, all after army service and university studies, currently range in age from 25-32 and are assigned to Hillel on campuses.

These young men and women, similar to other Jewish professionals on campus, are full-time members of the campus community and, as such, interact, live, and socialize there. They also actively create, administer, and participate in various programs related to Jewish life and Israel for the campus Jewish community. As we noted above, this affords them a unique perspective on judging the nature of antisemitic sentiment and anti-Israel activity on campus.

Our current study (conducted in January-February 2021), similar to our previous study on Hillel directors, sought to understand how these professionals view the antisemitism and anti-Israel issue and how it applies to their campus. We initially conducted a focus group with a smaller group of emissaries to clarify general issues and develop an approach to measuring the issue. This was followed by a wider anonymous internet survey of key questions.

Out of 60 professionals surveyed, 43 (71.6%) responded, with 39 (65%) completing the entire survey. This represents a significant representative sample of the population of emissaries. Our findings are summarized as follows:

- While the majority see antisemitism/anti-Israel activity as at least a “moderate” problem on campus in general, most also feel that only a “minority” of students are responsible for this activity.

- Most perceive that the problem on other campuses is significantly greater than on their own campus, with many seeing the problem on their campus, but not on other campuses, as “insignificant.”

- A majority clearly see Muslim or Arab students as well as “progressive” groups as most responsible for antisemitic/anti-Israel activity.

- Only 10% of our sample felt that the students they interact with feel “definitely intimidated or unsafe” on campus, with the majority indicating that they feel most students are only “very little” or “not at all” feeling intimidated or unsafe.

- According to our sample, the most cited factor in feeling “intimidated or unsafe” on campus are statements made by a faculty member. Physical attacks are almost non-existent, with our sample split between citing verbal abuse and a “general atmosphere” on campus as reasons for students’ perception of intimidation or feeling “unsafe.”

- Some politically liberal or progressive organizations (such as “Black Lives Matter”) were perceived as generally unsupportive of Jewish students on campus, with more conservative organizations seen as more supportive.

- Over 40% of our sample felt that national Jewish organizations “exaggerate” the level of antisemitism or anti-Israel sentiment on campus, while 25% felt it was “underestimated.”

Comparison with the 2015 Hillel Sample

While both surveys were not identical, there were several questions that were. Moreover, we can identify some general themes that appear to be consistent between these two samples, despite the difference of seven years between surveys and a different “type” of campus professional in each survey. The most consistent, overriding theme appears to be the discrepancy between the general public perception of widespread and/or significant antisemitic /anti-Israel activity on campus and our data based on the perception of campus professionals indicating that the issue is not a wholesale one and needs more precise campus identification.

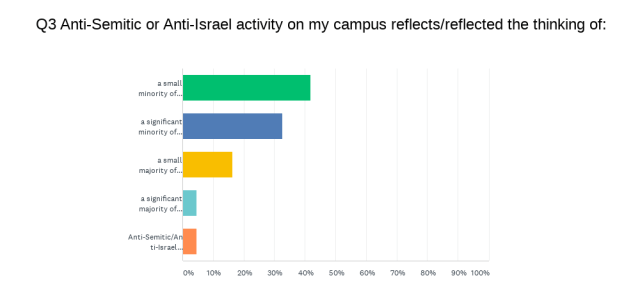

In 2015, 71% of the sample (of 59 respondents) felt that “antisemitic” activity reflects the thinking of a “minority” of students on campus (61% cited “a small minority”). With regards to “anti-Israel activity, over 70% felt this way as well.

In our current (2021) sample of Israeli campus professionals, we see over 70%, almost identical to the 2015 sample, responding similarly, i.e., that antisemitic or anti-Israel activity reflects the thinking of a minority of students (see table below).

Both samples also showed a similar discrepancy in their perceptions of hostile activity on their campus as compared with other campuses. In 2015, while about 85% of the sample felt that anti-Semitic sentiment on their campus was either “very little, insignificant” or “none at all,” only about 27% felt this way about other campuses. The same was true when it came to the perception of specifically anti-Israel sentiment, with the discrepancy between one’s own campus and other campuses being about 71% versus 23%.

In our current sample, we found similar discrepancies in perception of hostile activity between one’s own campus and other campuses; 52%-2% for antisemitic activity and 42%-4% for anti-Israel activity (see table below).

When it came to the perception of “intimidation of feeling unsafe,” less than 5% of our 2015 Hillel sample felt students were “very much” or “definitely” intimidated or unsafe on campus, with about 90% feeling students are either “not at all” or “very little” intimidated or feeling unsafe. In our current sample, we also see only 10% stating that students were “very much” or “definitely” intimidated or unsafe on campus. While the majority of students (52.5%) still felt “not at all” or “very little” intimidated or “unsafe,” this represented a lower amount than cited by the 2015 sample of Hillel professionals. There was also a rise in the perception of students feeling “moderately” intimidated or unsafe from 6% in the 2015 sample to 37.5% in our current sample.

When we asked in 2015, “What drives anti-Israel activity on your campus?” we found that 53% felt that “Muslim or Arab students on campus” contribute to this at least a moderately significant amount, with 58% citing that students belonging to “progressive” or “revolutionary” groups also contribute at least to a moderately significant level. Our current sample was asked a slightly differently worded question with an additional choice of “right-wing groups” added. The results (table below) also show significant levels with Muslim or Arab students (over 73%) but clearly trending to greater levels of significance. Our question regarding “progressive” groups (we did not use the additional term “revolutionary”) showed over 87% noting at least moderate significance, again trending toward higher significance with almost 60% indicating ‘fairly high” or “very high” amount of significance.

Here are the responses to the question: “To the best of your knowledge, what is your estimate, on a scale of 1-5, of the following factors behind antisemitic or anti-Israel activity on your campus.”

Answered: 41 Skipped: 2

In 2015, a large amount (almost 80%) of our respondents felt that pro-Israel advocacy organizations “exaggerate” to some extent the level of antisemitic or anti-Israel sentiment on campus. Our current sample (see table below) also showed many who felt similarly, but it did not approach the high level of the 2015 sample. It is important to clarify that this finding does not speak to the actual perceived level of this activity or sentiment on campus but only points to a perception that there may be a better way of presenting the phenomenon. While about the same amount felt the organizations do accurately portray matters (25% in 2015 vs. 33% in the current sample), many more of our current sample felt the level of activity is underestimated (25% in the current sample vs. only about 4% in the 2015 sample).

Our current sample was also probed on several other issues.

We were interested specifically in how they felt regarding the support of specific, politically identifiable groups on campus for Jewish students. Here we found, consistent with the more general question (above), that more liberal “left” groups (including Jewish left-wing groups) were considered less supportive while more conservative “right” groups generally were more supportive (see table below).

We tried to better understand the reality behind the popular use of the term “feeling unsafe” on campus by probing the type and number of antisemitic attacks. Our current sample reported practically no actual physical attacks, with verbal abuse or a general “atmosphere” of feeling unsafe reported by over 90% of the sample. Over 67% reported a faculty member’s statements in class as prompting feelings of intimidation or being “unsafe” (see table below).

What Do Our Findings Tell Us?

While there are similarities as well as differences between our two samples, we need to keep in mind that the samples are not only of data probed seven years apart, but also of professionals that, while both serving the Jewish community on campus, are separated by cultural perspectives with one group being (generally older) Jewish-Americans well into their careers and the other (generally younger) Jewish Israelis just beginning.

By looking at both samples, we can compare the findings that are consistent and thus reinforce the strength of any conclusions we may draw.

For example, both in 2015 and currently, we see that some groups identified as liberal or progressive are perceived as not supportive of Jewish students. Furthermore, groups such as “Black Lives Matter” are now specifically noted for their lack of support, despite the general support for BLM reported among Jewish Americans.14 While the findings of the present study came long before the latest Israel-Hamas confrontation in May 2021, subsequent declarations by BLM appear to buttress this piece of data, as explained in a Washington Post report15 with the headline: “From Ferguson to Palestine”: How Black Lives Matter Changed the U.S. Debate on the Mideast.”

Another important finding is the distinct differentiation in perception regarding one’s own campus as opposed to other campuses (again, similar in both samples). This also may tell us that the approach of painting all campuses with the same brush of antisemitism or anti-Israel sentiment may be as unproductive as it is inaccurate. It also may tell us that the issue, as presented in the Jewish world, may present an incomplete and mistaken picture. While such activity clearly does exist on some campuses, it also clearly does not exist on many (more) others. As one of our current survey responders commented, “Israel advocacy orgs (sic) … give attention to insignificant efforts and therefore insert fear into the campus community.” In effect, targeting efforts at dealing with specific campuses where issues are actually present may be critical in developing strategies for Jewish campus activism.

Another possibly important finding is the feeling that faculty behavior in class creates an atmosphere that makes Jewish students uncomfortable. Identifying and targeting these individual faculty members would appear to be indicated as part this strategy as well.

In summary, in providing guidance for the pro-Israel community, we can focus on:

- Understanding that specific campuses rather than the “campus” in general are problematic. Broad generalizations in describing campus issues may not be productive.

- Understanding that while liberal and left-leaning Jewish Americans seem to be in the majority, some social and political groups they identify with are perceived as unsupportive of Jewish students on campus. Consequently, community education on this issue would be needed.

- While Israel is often targeted on many campuses, the issues ultimately are seen by campus professionals as linked to antisemitism and not with a specific concern with Israeli actions.

- Faculty, rather than (or in addition to) other sources, should be focused on dealing with hostile campuses.

In reviewing these findings, keep in mind that the data represent reflections of individuals who are campus professionals and not merely general Jewish activists. The perspective of these individuals should thus carry more weight than sporadic and fleeting reports of events and incidents that may take place on different campuses. Both of our samples show similar trends where impressions of the level and extent of antisemitic sentiment and anti-Israel activity on the campus, in general, appear to be greater than actually exists. Certainly, this does not mean that antisemitic and anti-Israel activity does not exist. On the contrary, it may be that Jewish activist organizations may be inappropriately generalizing the problem rather than accurately targeting campuses and faculty where more marked anti-Israel and antisemitic sentiment exists. Speaking broadly of a “problem on campus” may not be productive and serves to distract and divert attention from what should be more specified targeting of campuses that deserve attention.

We also may need to confront the notion, common among liberal Jewish Americans, that right-wing sources are mostly responsible for antisemitism, leaving more liberal and progressive organizations immune from criticism. In fact, our data showed that it is some of these very liberal and progressive groups (and apparently faculty sympathetic with them) that are felt to be less supportive of the Jewish student and thus more responsible for the atmosphere of antisemitic and anti-Israel sentiment (which much of our campus professionals see as synonymous) that exists on certain campuses. Confronting the liberal-progressive-driven individuals and groups that are unsupportive of Jewish students and critical of Israel may be helpful in countering anti-Israel attitudes. However, given the left-progressive general acceptance of the Jerusalem Declaration of Antisemitism’s exceptions for much anti-Israel activity, including opposing Zionism and supporting BDS, it appears that many Jewish-Americans who identify with progressive movements will not support the above conclusion. Indeed, judging by the list of signatories of the declaration, this appears to be the case. One recent poll,16 showing that 25% of American Jews see Israel as an “apartheid” state, is yet one more indication of the current ideological tendency of the Jewish-American community. While some have challenged the results of the poll as biased and tendentious,17 the findings may not be inconsistent with findings of our own showing that significant sectors of current Jewish-American thinking look at Israel quite critically.18

Hence, given the political and social attitudes characterizing much of the Jewish American community, effecting change based on confronting attitudes from the progressive left would appear to represent a significant albeit essential challenge.

* * *

Notes

The author gratefully acknowledges the invaluable support of Michelle Rojas-Tal of the Jewish Agency/Hillel in conducting this study and in interpreting the results.

Editor’s note: The Associated Press stylebook now says to write antisemitism and antisemitic without a hyphen and with no capital “S.” (https://www.cjr.org/language_corner/associated-press-stylebook-2021-changes.php)

1 https://www.adl.org/what-we-do/anti-semitism/antisemitism-in-the-us

2 https://www.adl.org/think-plan-act

3 https://www.jpost.com/opinion/how-can-jewish-students-fight-antisemitism-on-campus-653348

4 https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/09/09/anti-semitism-rise-new-semester-starts

5 https://www.state.gov/defining-anti-semitism/

6 https://jerusalemdeclaration.org/

7 https://www.holocaustremembrance.com/sites/default/files/press_release_document_antisemitism.pdf

8 https://www.brandeis.edu/cmjs/birthright/antisemitism.html

9 https://www.bjpa.org/search-results/publication/22206

10 https://www.adl.org/resources/reports/antisemitism-and-the-radical-anti-israel-movement-on-us-campuses-2019

11 https://www.ajc.org/translatehate/From-the-River-to-the-Sea

12 Mansdorf, I.J. The “anti-Israel/anti-Semitism” phenomenon and Jewish Campus Professionals What do they think? unpublished survey, May 1, 2015.

13 https://www.jewishagency.org/campus-israel-fellows/

14 https://jcpa.org/article/american-jewry-in-transition-how-attitudes-toward-israel-may-be-shifting/

15 https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/gaza-violence-blm-democrats/2021/05/22/38a6186e-b980-11eb-a6b1-81296da0339b_story.html

16 https://www.jewishelectorateinstitute.org/july-2021-national-survey-of-jewish-voters/

17 https://besacenter.org/jews-gaslighting-jews-a-primer/

18 https://jcpa.org/article/american-jewry-in-transition-how-attitudes-toward-israel-may-be-shifting/