INTRODUCTION

The symbolic moment when the now ubiquitous phrase “tikkun olam” entered the American Jewish mainstream probably took place during the visit of Pope John Paul II to the United States in September 1987. A crisis in Vatican-Jewish relations was precipitated by the Pope’s meeting in June with President Kurt Waldheim of Austria, whose activities as a Nazi intelligence officer were the subject of controversy. The meeting in Miami between Jewish leaders and Pope John Paul II on September 12, 1987 was meant to signal the desire of both sides to embark on a process of repairing their relations. In his public remarks to the Pope in Miami, the leader of the Jewish delegation, Rabbi Mordecai Waxman, chairman of the International Jewish Committee on Interreligious Consultations, called for a spirit of reconciliation and goodwill. “A basic belief of our Jewish faith is the need ‘to mend the world under the sovereignty of God’—‘l’takken olam b’malkhut Shaddai,’” Waxman declared: “To mend the world means to do God’s work in the world. Your presence here in the United States affords us the opportunity to reaffirm our commitment to the sacred imperative of tikkun olam, the mending of the world.”2

Waxman’s remarks were notable mainly because he mentioned the term “tikkun olam” in public. By the mid-1980s, rabbis, educators, communal workers, activists and others were invoking tikkun olam as a value concept in support of a variety of humanistic and distinctly Jewish causes, ranging from environmentalism and nuclear non-proliferation to Palestinian-Israeli reconciliation and unrestricted Soviet Jewish emigration.3 For the most part, however, its use was confined to internal American Jewish discourse. Waxman’s introduction of tikkun olam to a broad international audience indicated the extent to which the term had become embedded into the fabric of American Jewish life. Before long, tikkun olam found its way into the pronouncements of non-Jewish public figures such as New York Governor Mario Cuomo and became the rhetorical motivation for service learning and social justice organizations such as AVODAH, American Jewish World Service and Panim el Panim. “Tikkun” also radiated from the masthead of a new, self-consciously intellectual, progressive Jewish magazine. By the 1990s, tikkun olam was everywhere.4

THE EVOLUTION OF THE MEANING OF TIKKUN OLAM

At the time, Waxman’s identification of tikkun olam as a “basic belief of our Jewish faith” was remarkable. While the term may be traced back to Talmudic texts and the early post-Temple liturgy and it later played an important role in medieval Jewish mystical tradition, the meaning of tikkun olam has evolved over time. The contemporary connotation, with its emphasis on human agency in bringing about God’s kingdom on earth, represents both a synthesis and reinterpretation of earlier conceptual frameworks and a response to the perceived failure of the modern Jewish experiment.

Moreover, although by the eleventh and twelfth centuries it was invoked thrice daily in the liturgy, tikkun olam remained a fairly obscure notion until it was appropriated by the kabbalists. While Jews always were concerned with social justice, its association with tikkun olam is hardly a century old and was not widely adopted in North America until the 1970s and 1980s. Waxman’s translation of tikkun as “mend” (as opposed to the more common “repair” or “perfect”) and the centrality of the Holocaust to the interfaith dialogue with the Vatican, may indicate his indebtedness to theologian Emil Fackenheim, whose influential work of post-Holocaust theology, To Mend the World, appeared in 1982.

The extent of the meteoric ascent of tikkun olam can be traced by using the Google Books N-Gram Viewer.5 Google Ngram is a phrase usage graphing tool; it charts the usage of letter combinations (e.g., words and phrases) year after year, utilizing Google’s extensive database of over 500 billion words from nearly 5.2 million digitized books published between 1500 and 2008.6 A database search (see: Chart 1) found no matches for the terms “tikkun olam,” “tikun olam,” “tikkun ha’olam,” and “tikkun ha-olam” prior to 1946. In fact, they barely registered before 1970. After 1980, however, the incidence of “tikkun olam” grew steadily until 1992, when the increase in rate of frequency jumped even more dramatically before reaching a plateau in 2002.

The increasing use of tikkun olam may be attributed partly to a more general trend over the past thirty years of incorporating Hebrew terms into American Jewish discourse. Consider, for example, the platforms of American Reform Judaism. The 1885 Pittsburgh Platform contains no Hebrew words and the 1937 Columbus Platform includes a single Hebrew word, “Torah,” which appears in English transliteration. Even the 1976 San Francisco Platform contains only two Hebrew words, Torah and aliyah, immigration to Israel, both of which are transliterated. In contrast, the 1999 Statement of Principles contains some twenty distinct Hebrew words or phrases, rendered both in Hebrew characters and in English transliteration.7

Basic Hebrew words such as Shabbat, mitzvah and shalom witnessed a dramatic rise in usage between 1950 and 2000, especially between 1980 and 2000. The reasons for this increase include the influence of the State of Israel, the growing acceptance and even chic of ethnic distinctiveness in general American culture, the resurgence of Orthodox Judaism, the influence of former havurah (autonomous alternative to established Jewish institutions and denominations) and Jewish counterculture leaders upon mainstream Jewish organizations, and the increased concern with maintaining ethnic and religious survival.8

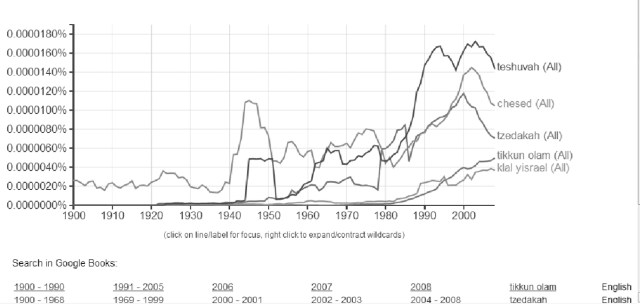

In the case of tikkun olam, however, the above only explain part of the increase. Consider, for example, an Ngram graph of five fairly common contemporary Jewish value concepts between 1900 and 2008: teshuvah (repentance), chesed (grace or compassion), tzedakah (philanthropy), Klal Yisrael (Jewish unity and peoplehood), and tikkun olam (see: Chart 2). While all reflect the general trend of increased usage of Hebrew terms, to some extent, tikkun olam is a latecomer. The other four terms came into use by the late 1920s, whereas tikkun olam first appeared in English-language books and magazines a generation later. Also noteworthy is the decline in the use of terms such as teshuvah, chesed and tzedakah shortly after 2000. In contrast, tikkun olam, and to a lesser extent, Klal Yisrael, became more popular between 2000 and 2008, although neither reached the rate of use of the former three terms. Both the late emergence and the unabated growth in the popularity of tikkun olam require further explanation.

In this article, I hope to contribute to our understanding of the contemporary use of tikkun olam by exploring its emergence in the United States during World War II and its subsequent appropriation by various public intellectuals, educators, activists and communal workers between the late 1950s and the early 1980s. The association of tikkun olam with human agency, a human-centered utopian quest to realize God’s Kingdom on Earth, most likely originated a half-century earlier among the early Zionist colonists, whose embrace of modern nationalism and the New Yishuv in Palestine as a response to anti-Semitism, economic deprivation, and the failure of liberalization policies in czarist Russia defied the conventional Jewish teaching that only God could initiate the ingathering of the Exiles and the messianic era. It acquired a new meaning, however, as American Jewry struggled to come to terms with the implications of the Holocaust and the mission of American Jewry in a post-Holocaust world.

As I argue below, there were three distinct, albeit occasionally overlapping, groups that were instrumental in popularizing tikkun olam in the postwar period: theologians, troubled by the implications of the Holocaust, found in tikkun olam a useful concept for re-imagining the covenantal relationship between humans and God; educators in the 1960s, who, when confronted by the counterculture of the youth, gravitated to tikkun olam, with its idealistic connotations, as part of a larger effort to align the teaching of Jewish values with contemporary concerns; and finally, social activists and havurah members concerned about what they perceived as the conservative and inward-oriented drift of the American Jewish community. By the end of the twentieth century, tikkun olam was widely acknowledged as a central Jewish tenet and even as a rationale for Jewish survival.

THE EMERGENCE OF TIKKUN OLAM AS A MODERN-DAY IDIOM

Several scholars have traced the evolution of tikkun olam in classical and medieval Jewish sources. We shall mention their studies here for the purposes of context.9 The idiom made its debut in early rabbinic literature, and most notably in the second paragraph of the contemporaneous Aleinu prayer. In the Talmud, where it appears thirty-eight times, the justification of mipnei tikkun ha-olam, for the sake of the improvement or stabilization of society, was applied to rabbinic enactments that were designed to close loopholes perceived as damaging to the credibility of the legal system as a whole. Mipnei tikkun ha-olam appeared most often in association with divorce law but was also occasionally extended to the economic realm. The best-known case involved the prozbul, the amelioration of unintended financial consequences ensuing from the cancellation of debts during the sabbatical year. In all of these instances, tikkun olam applied only to Jews.10

In contrast to the Talmudic application of tikkun olam by leading rabbis who made legal decisions for the betterment of Jewish society, Aleinu envisions the repair of the world under the Kingdom of God, l’taken olam b’malkhut Shaddai. While this understanding of tikkun olam was more universalistic, its concept of repair as the eradication of paganism and the imposition of religious uniformity is far removed from the modern concept of social betterment. Moreover, Aleinu did not explicitly conceive of a role for Jews or for humanity in general in this eschatological drama, save for bearing witness. The connotation of tikkun olam moved from “this-worldly” in the Talmud to “other-worldly” in the liturgy.11

After the redaction of the Babylonian Talmud, tikkun ha-olam was not used frequently in legal and liturgical texts until the thirteenth century. Then, the kabbalistic work, the Zohar by Rabbi Moses de Leon effectively introduced the idea that human beings could repair the “the flaws in the universe… and help restore the cosmic balance.” It was the thought of Isaac Luria (1534–1572), however, that fully elaborated the mystical meaning of tikkun olam. The kabbalistic iteration of tikkun olam radically differs from both the Talmudic and third-century liturgical understanding of the idiom. Luria envisioned human beings as full partners with God in bringing redemption. While both the Aleinu and the Lurianic creation myth were eschatological, the Lurianic notion of redemption imagined a reunification of the Godhead and an end to the material world.

Luria’s gnostic outlook caused him to reject the present world as fundamentally wicked. Humanity essentially was asked to pave the way for the undoing of its creation. Finally, while both the Talmud and Luria saw a role for humanity in tikkun ha-olam, the rabbis mandated concrete ameliorative steps in order to strengthen the social fabric and promote economic justice, while Luria invested the power of tikkun in acts of contemplation, study and the performance of mitzvot.12

By the nineteenth century, tikkun ha-olam had largely fallen out of use. When it was revived in the twentieth century, its meaning had changed again. In North America, tikkun olam as it is understood today made its debut around 1940. In one of the earliest recorded usages in North America, leading Jewish educator Alexander Dushkin invoked tikkun olam during World War II. Dushkin valiantly made the case for the congruence of Jewish and democratic values. He insisted that the “inalienable rights” of “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” had their analogy in the Torah’s description of God’s attributes, including “justice and righteousness” and “freedom and loving kindness” to which humanity aspires. He added that while democracy “based its social relationships on the dignity of the individual” and envisioned an engaged citizenry pursuing the common good through “social service,” Jewish tradition was based upon “the conception of Man as both the child of God and the partner of the Almighty in tikkun ha-olam—the continuous task of reconstructing the world.”13

Dushkin, the executive director of the Jewish Education Committee of New York, returned to tikkun ha-olam in his later writings, most notably in 1945, when he included it among seven “Common Elements” that should be taught in Jewish schools of all denominations. He noted “a growing acceptance by Jewish teachers” that this value should be integral to their teaching, “so as to transfuse all their work with that faith which posits an ongoing purpose in the universe making for the betterment of the world and of mankind, and which involves the teaching of our obligations to strive to share in this continuing urge to betterment, this tikkun ha-olam.”14

The elevation of tikkun olam to a core value (along with Torah, Hebrew, mitzvot, Jewish peoplehood, Palestine and American-Jewish citizenship) was Dushkin’s attempt to add a spiritual component to his Common Elements. God was conspicuously absent from Dushkin’s curricular building blocks. “Faith in the divine purpose making for the betterment of the world and man,”15 was Dushkin’s most direct attempt to make God part of the conversation in the Jewish school.

Dushkin’s earlier invocation of tikkun olam, however, illustrates that his attraction to the concept should be considered in the context of the rise of Nazism and the American entry into World War II. Identifying Judaism and Jewish values with the war against fascism allowed a vulnerable and predominately immigrant community to display its patriotism by demonstrating the harmony between American and Jewish values. Of course, irrespective of America’s entry into the war, “the repair of the world” through the defeat of Hitler was also a profoundly Jewish interest.

As a student of Mordecai Kaplan and a member of the circle of rabbis, educators and communal workers which actively worked to spread Reconstructionism during the interwar years, Dushkin was familiar with Kaplan’s interpretation of the passage in Aleinu as a mandate for social activism. In The Meaning of God (1937), Kaplan asserted: “We cannot consider ourselves servants of the Divine King unless we take upon ourselves the task ‘to perfect the World under the Kingdom of the Almighty.’” It is clear that Kaplan did not regard the task to be exclusively or even mainly contemplative. He wrote about striving to “reconstruct the social order” and specifically focused on economic inequality, political corruption, a failing education system and the persistence of war. “We should not give up hope of achieving an adequately representative government integrally related to a righteous economic order and to an internationalism without which there can never be universal peace.” While Dushkin did not explicitly state that Kaplan (or any other thinker) shaped his understanding of l’taken olam, his closeness to Kaplan and the similarity of their thought suggest a possible connection.16

Dushkin probably was aware of Rabbi Eugene Kohn’s address to the Rabbinical Assembly in 1935. A disciple of Kaplan, Kohn dwelt upon the importance of education for social justice in the Jewish school and invoked tikkun olam in passing. He argued that ethical education should not only instruct students on the rules of “fair play,” but also should provide them with “standards for criticizing the rules and a sense of responsibility for cooperating with other individuals in the cause of tikkun olam.” It is difficult to know whether Kohn was using the idiom in the Talmudic sense of preserving the social order or whether he had in mind a more ambitious agenda of societal repair. The subsequent sections, however, speak more explicitly about “social improvement” and evoke the betterment of God’s kingdom on earth as a “this-worldly” messianic ideal, themes that were adopted and expanded by Kaplan.17

Even as he offered an activist interpretation of the passage in Aleinu, Kaplan acknowledged its novelty. The medieval mindset viewed redemption as the prerogative of God. Both Christians and Jews regarded humanity as irredeemable without divine intervention.18 Enlightenment thought and nineteenth century political ideologies maintained that human beings were masters of their own destinies. This outlook helped lay the groundwork for Jewish political and intellectual movements, such as Bundism and Zionism. Kaplan took note of the continuous resistance on the part of many Orthodox leaders to any human activity that was designed lidhot et ha-ketz, to hasten the redemption before God had resolved to bring it about.19 But his conviction that Judaism would need “to transform itself from an other-worldly religion, offering to conduct the individual to life eternal through the agency of traditional Torah into a religion that can help Jews attain this-worldly salvation,” was the underlying premise of his

work.20

Kaplan’s allusion to Zionism and other Jewish political ideologies is instructive. Interestingly, tikkun olam gained currency in Palestine in the early twentieth century. It was adopted by Jews of various political stripes in order to describe the most utopian manifestations of the Zionist project. To be a metaken olam, a perfecter of the world, was to embrace radical change. For example, during the Second Aliyah (1904–1914), tikkun ha-olam was used to articulate the motivations of the members of the earliest cooperative settlements.21

Later, it became an important component of the teleology of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, the first Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of Palestine. As Ben-Zion Bokser explained, Kook saw Judaism as instrumental in hastening human enlightenment:

For Rabbi Kook, the essence of Judaism, which flows from Jewish monotheism, is the passion to overcome separatism, the severance of man from God, of man from man, of man from nature. It is the passion to perfect the world through man’s awareness of his links to all else in existence.

Kook declined to see a binary opposition between the material and the spiritual worlds or between Israel and the other nations, teaching that there was holiness in all of creation. Furthermore, he regarded penitence as a means to tikkun, and a reunification with God. While penitence begins with the quest for self-perfection, it ultimately “overflows into the endeavor to perfect society and the world.”22

Even more controversially, from the perspective of many Orthodox leaders of his day, Kook’s teachings about tikkun and his perception of holiness of all of humanity became a springboard for a redemptive religious Zionism. He embraced the secular Zionists’ rebuilding of Eretz Israel as a holy project and regarded them as (unwitting) agents of messianic redemption and tikkun. According to Michael Prior, “Rav Kook’s writings and teachings provided the first systematic attempt to integrate the passive religious longings for the land with the modern, secular and aggressively active praxis of Zionism, giving birth to a comprehensive religious-nationalist Zionism.”23 Rav Kook’s understanding of tikkun, however, derived more from his reading of kabbalistic and hasidic sources than from its usage in secular Zionist circles.24

Levi Cooper has shown that the political activist connotation of tikkun olam was not confined to secular and religious Zionists. In 1932, a work by propagandist Alter Hayim Levinson, entitled Tikkun ‘olam, enjoined fellow Jews to support the religious anti-Zionist Agudath Israel party (founded in 1912). Ironically, an attack on the political activist stance of the Agudah, and the Zionists in particular, published under the imprimatur of the Munkaczer Grand Rebbe Hayim Elazar Spira (Shapira), was also entitled Tikkun ‘olam.25

Unlike Kaplan, who based his explanation of tikkun olam upon liturgical and Talmudic texts, Kook’s philosophy, while novel, was heavily indebted to Lurianic teachings. What both thinkers held in common, however, was a rejection of Jewish passivity, which they considered untenable in contemporary circumstances.

REPAIRING THE WORLD AND THE COVENANT DURING AND AFTER

THE HOLOCAUST

At the same time, another rabbi embraced an activist, this-worldly understanding of tikkun olam when confronted by catastrophe. Liberal Rabbi Leo Baeck led the representative body of German Jewry, the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith from 1933 until it was disbanded in 1938. His student, Emil Fackenheim, vividly recalled Baeck’s sermon on the Aleinu prayer in the mid-1930s: “He preached about the abomination of the false gods, and everyone present knew what he had in mind,” and “ended up with the subject of tikkun olam.” Fackenheim noted that while the term could be translated in a variety of ways with messianic undertones, Baeck preferred a “more sober” interpretation: “preparing the world for the kingship of God.” It was the responsibility of Germans and the world as a whole to facilitate the emergence of a more perfect future by sweeping away the abomination of Nazism.26

The impact of Hitler’s oppression of the Jews on Baeck’s interpretation of tikkun olam anticipated the way in which the term often was used in the decades after World War II. In 1949, Rabbi Abraham J. Feldman, longtime spiritual leader of Congregation Beth Israel in West Hartford, was asked to deliver the Saturday morning sermon at the Sixth International Conference of the World Union for Progressive Judaism. Speaking from the pulpit of the Liberal Jewish Synagogue in London, Feldman chose to take stock of Liberal Judaism, particularly its “mission idea,” in the aftermath of the war. Jews and humanity in general were living in “erets tsalmaveth, the land of the shadow of death,” Feldman declared, and the road to fulfillment and redemption lay in “tikun olam, the establishment of God’s kingdom for social stability.” As a Reform rabbi, Feldman maintained that only a “dynamic Judaism rooted in the past,” but open to the “modification of techniques of religious living,” had the potential to reenergize Jewish life. He closed his remarks with an affirmation that the mission of Israel remained what it had always been: “l’taken olam bemalchut Shaddai—to give permanence and stability to society by establishing the kingdom of God on earth amongst men. We have no other goal. Judaism has no other aim.”27

Feldman’s use of tikkun olam to characterize the mission idea of the Reform movement was novel in the immediate postwar era. Reform leaders and official Reform statements usually referred to “social action” or “social justice.” In fact, as Michael Meyer and Gunther Plaut have observed, the first Union of American Hebrew Congregations (UAHC)28 statement to link the Jewish prophetic heritage to social justice was published only in 1955. While the first sentence of that statement alludes to the Aleinu prayer by defining the ultimate goal of Judaism as “the establishment of the Kingdom of God on earth” and its conclusion quotes the final sentences of the prayer, it does not explicitly call for the repair of the world, either in Hebrew or in English. Rabbi Eugene Lipman, who led the UAHC’s Commission on Social Action between 1953 and 1961, later regretted that the UAHC did not refer to rabbinic sources in its declarations regarding social justice.29

The linkage of tikkun olam with post-Holocaust healing and revival emerged particularly after the trial of Adolf Eichmann which encouraged more public discussion of the Holocaust. While, during the 1960s, theologians cautiously raised the question of theodicy, Stephen Whitfield pointed out that the sheer “magnitude and incomprehensibility” of the genocide dissuaded many from confronting it directly.30 Some focused primarily on the human response to the apparently circumscribed power of God. According to S. Daniel Breslauer, “post-Holocaust theology has as one of its major components the need to create a new moral and ethical ideal for a humanity shaken to its roots by its own destructive power.”31

For many of these thinkers, covenant theology had a special appeal. Based on the (ancient Near Eastern and) biblical concept of brit (covenant), it presumed “mutuality in the relationship between God and Israel.”32 Eugene Borowitz, who popularized the term in an article in Commentary in 1961, asserted that the paradigm of covenant provided Jews with a reason for continued righteousness even as it rationalized the ubiquity of sin.

Religion always involves two partners, God and man. Jewish history has seen the doleful results of overemphasizing the role of either. The reliance upon God alone in times of oppression and persecution has often acted to reduce the role of mitzvah, to relieve the people of its responsibility to use its own powers for justice and peace. And the insistence upon man as the master of history explains the continuing stream of false Messiahs and of the spiritual ordeal which inevitably follows their exposure.

Having affirmed the eternity of the covenant, Borowitz continued that the task of the Jew entails the sanctification of time and the redemption of history through the performance of mitzvot.

Each Commandment becomes a way not only to personal improvement and fulfillment, but also helps to satisfy his responsibility to God and to mankind. Similarly, in performing the mitzvoth he makes his own life more holy and brings the world that much closer to the Kingdom of God.33

Borowitz resorted to conventional arguments about free will in relation to

theodicy (a vindication of God’s goodness and justice in the face of the existence of evil) and, in subsequent arguments, posited the imperative of a transcendent standard of holiness as a case against the death of God. Some considered this inadequate.34 Nevertheless, covenant theology (originally a Calvinist set of ideas for interpreting the biblical narrative) influenced the thinking of post-Holocaust theologians, from Eliezer Berkovitz to Richard Rubenstein, who presented a variety of views about theodicy and the relationship of God to the Jewish people.35 Whereas Borowitz invoked the language of mitzvah in articulating humanity’s role in this sacred partnership, others preferred tikkun olam, an idiom that was more elastic, more sweeping, and suggested a joint endeavor in which both the divine and the human were complementary. Tikkun olam was preferable because it implied the brokenness of the world. It gave expression to the bafflement that Jews felt as they sought to grapple with what was seemingly inexplicable.

One of the earliest public intellectuals to invoke tikkun olam in his response to the Holocaust was Harold Schulweis, a leading Conservative rabbi and the spiritual leader of Valley Beth Shalom in Encino, California.36 In a symposium entitled “The Condition of Jewish Belief,” which appeared in Commentary in 1966, Schulweis insisted that the world was “created imperfect and incomplete.” Humanity was tasked with being “an ally of God in perfecting and repairing the incomplete world (tikkun olam).” Schulweis went even further and urged men to follow the example of Abraham and confront God with examples of divine moral lapses. As human beings were “endowed with an imago Dei,” rather than “helplessly fallen,” Schulweis expected them to “exercise [their] moral freedom and responsibility in the world. The high status conferred upon man as a morally competent partner of God produced and still cultivates a social consciousness and activism in the knowledgeable Jew.”37

Placing social action in the framework of covenant, Schulweis regarded tikkun olam as part of the tradition of Jewish “struggle,” as well as the brokenness of the world. He explicitly maintained that tikkun olam demanded this-worldly activism. Judaism must open itself “to those interests—economic, social, cultural—more often relegated to the secular in doctrinally-centered theology.” Furthermore, his insistence that the covenant was “people-centered,” meant that social justice was a communal responsibility as opposed to a solitary endeavor. Likewise, he argued that salvation would be realized collectively, not individually. In Evil and the Morality of God Schulweis developed the concept of “predicate theology” as a response to the problem of theodicy in the wake of the Holocaust. The divine was made manifest in the actions of humanity.38

Schulweis was deeply concerned with the educational implications of his theology, particularly in light of the Holocaust. In an essay on Holocaust education, written in 1963, he called for teaching about acts of heroism undertaken by Gentiles in rescuing Jews during the Holocaust along with “the terrible truth [of] man’s awful capacity to hurt and to destroy.” This conviction, which ultimately inspired his founding of the Jewish Foundation for the Righteous in 1986, was based upon the belief that educators must cultivate in their students an impulse to social activism. Schulweis argued:

Morality needs evidence, hard data, facts in our time and in our place to nourish our faith in man’s capacity for decency. Wisdom calls for a moral otology [study of the anatomy and physiology of the ear]: how to make one hear the unpleasant truth without destroying his sensitivity to the still, small voice of conscience and hope.

To destroy humanity’s faith in its own capacity for goodness would be to give up on its partnership with God: “Tikkun olam—the improvement of this world expresses the theistic humanism and activism of our tradition…. We are children of prophets, creating conditions for a better future.”39

Schulweis’ social activist orientation regarding repairing the world contrasts with that of Emil Fackenheim, another post-Holocaust theologian whose struggles with covenant led him to tikkun olam. To be sure, resistance is a central motif in Fackenheim’s work, particularly in To Mend the World, which appeared in 1982. The resistance of Hitler’s victims during the Holocaust inspired and demanded living a “resisting life” in its aftermath. Yet Fackenheim’s posture was inward rather than universal. His call for resistance in the shadow of complete rupture was a plea for Jewish survival. The will to live as a people, as exemplified by the creation of the Jewish state, and the reclamation of the principle that human life is sacred constituted acts of tikkun.

It is true that because a Tikkun of that rupture is impossible we cannot live, after the Holocaust, as men and women have lived before. However, if the impossible Tikkun were not also necessary, and hence possible, we could not live at all.40

For the kabbalists whose conception of tikkun olam inspired Fackenheim, it was the practice of “Torah, prayer and mitzvot,” their “impulse below,” that beckoned an “impulse from above.” Fackenheim expanded tikkun to include all acts of “kiddush ha-hayyim,” the sanctification of life.

Whereas Schulweis drew inspiration primarily from the Aleinu, Fackenheim was attracted to the teachings of Lurianic kabbalah as interpreted by Gershom Scholem (although, as we have noted, he was inspired by Baeck’s activist interpretation of Aleinu as well). Lawrence Fine pointed out that Fackenheim appropriated Lurianic themes in order to express ideas that were derived essentially from his earlier work. Fackenheim acknowledged his debt to Scholem in a footnote in To Mend the World and admitted that his interest in kabbalah “assumed real seriousness only with the present work.” However, Schulweis and Fackenheim both insisted on a this-worldly tikkun, a distinction that separated Fackenheim from traditional Lurianic teaching.41

Another post-Holocaust thinker who did much to popularize tikkun olam as part of his efforts to Judaize American Jewish civil religion was Irving Greenberg. A maverick modern Orthodox rabbi who began his career as an academic and a pulpit rabbi, Greenberg became a champion of Jewish religious pluralism and a spiritual advisor and teacher to a generation of Jewish communal leaders when he served as the first president of the National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership (CLAL), which he co-founded with Elie Weisel and Rabbi Steve Shaw.

In addition to his personal magnetism and gentle charisma, Greenberg was convincing because he articulated a meaning and purpose to the American Jewish polity’s survivalist agenda. Like Schulweis and Fackenheim, Greenberg’s wrestling with the impact of the Holocaust on God’s covenant with Israel led him to emphasize a this-worldly tikkun, “a final redemption within human history—not beyond it.”42 Greenberg agreed with Fackenheim that the Holocaust entailed a rupture, the abrogation of the Sinaitic covenant. He stated that “covenantally speaking, one cannot order another to step forward to die.” However, it was replaced with a “voluntary covenant,” whereby the Jewish people renewed its relationship with God not out of a sense of obligation but because it “was so in love with the dream of redemption that it volunteered to carry on with its mission.”

In this post-Holocaust covenant, the Jews were not merely partners with God but “senior partners in action,” entirely responsible for the execution of the covenant. “God was saying to humans: you stop the Holocaust. You bring about redemption. You act to ensure that it will never again occur.” According to Greenberg, the essence of the covenantal mission was to “create a redemptive model society.” He added that in an era of voluntary covenant one could not wait for the coming of the Messiah and that it was inconceivable that God could have, but chose not to send a redeemer during the Holocaust. In a paraphrase of Elie Wiesel’s Gates of the Forest, Greenberg argued: “Any Messiah who could have come and redeemed us, and did not do so then but chooses to come now is a moral monster.” Rather, Jews (and humanity in general) must be agents of their own redemption.43

For Fackenheim, Jewish survival was in and of itself a tikkun. Greenberg, however, viewed survival in instrumental terms, and tikkun olam as the ultimate goal. He explained that in the Jewish tradition, the Israelites, tasked with being a “kingdom of priests and a holy nation,” were the agents of God’s redemptive plan. They would achieve tikkun olam through their example of holy living. In the post-Holocaust world, Greenberg believed that this role would be assumed most of all by the Jewish state. “The reborn State of Israel is this fundamental act of life and meaning of the Jewish people after Auschwitz. Israel, as a Jewish-run reality, can exemplify the joint process of human liberation and redemption.”44

This idea actually implied a secularization of the Jewish mission. In an era when God was hidden from the world, the thrust of Jewish activity would have to be in the secular realm.

To restore the credibility of redemption, there must be an incredible outburst of life and redeeming work in the world…. The State [of Israel] shifts the balance of Jewish activity and concern to the secular enterprises of society building, social justice and human politics. The revelation of Israel is a call to secularity; the religious enterprise must focus on the mundane.45

Consequently, Diaspora Jewry’s financial support of Israel—a central function of United Jewish Appeal and the Federations—was not merely philanthropy, but an act of tikkun. Greenberg, however, also presumed a more direct role in tikkun olam for Diaspora Jewish communities. In the American Jewish context, the federations and communal agencies involved with defense, welfare and communal relations achieved post-Holocaust tikkun through their two-pronged domestic mission: assuring American Jewish communal welfare and Jewish cultural renewal and working for general social betterment in America and throughout the world. Greenberg took exception to the denigration of “checkbook Judaism.” The defense and welfare agencies were perceived as “affirmations of the dignity and value of Jewish lives.” Their major weakness was that they were not designed to articulate explicitly the principles that bolster Jewish continuity.46

By the 1970s and 1980s leading agencies were responding to this criticism by intensifying their efforts to transmit Jewish values, particularly by increasing support for educational and cultural endeavors. They were also articulating their social welfare and social justice agenda using terms of Jewish values. Greenberg’s message was embraced enthusiastically by a generation of baby boomers who assumed the leadership of the major Jewish organizations in the 1980s and 1990s. For example, executive director of the UJA Federation of New York, John Ruskay, was a veteran of the Jewish counterculture and havurah movement of the late 1960s and 1970s. He and his contemporaries followed Greenberg’s message of achieving this-worldly, universal objectives through particularistic instruments. Moreover, they had experienced firsthand the power of Jewish values and a participatory Judaism that enhanced their Jewish identity. Ruskay’s relationship with Greenberg dated back to the 1970s when he served as executive vice president of CLAL’s predecessor, the National Jewish Resource Center.

Greenberg won a following among Jewish communal professionals and lay leaders by elevating their sense of purpose and articulating their role in an uplifting way. It seemed as if he had become “the most popular and sought-after speaker on the federation lecture circuit.” His stature as an advisor, teacher and public intellectual greatly increased after the establishment of CLAL, which he made into an unofficial think tank for Jewish policy makers and community leaders. According to Steven Bayme of the American Jewish Committee, “in effect, Greenberg became a national rabbi for federation leadership providing Jewish content at federation events and anchoring federation activity in Jewish teachings.”

In teaching “an entire generation of federation activists to think and visualize themselves in more Judaic terms,” Greenberg helped introduce and popularize a “vocabulary” of Jewish value-concepts. Ruskay and likeminded communal leaders, such as Barry Shrage in Boston, became Greenberg’s apostles. Thus, by the 1980s and 90s Hebrew terms such as tzedakah and tikkun olam began to appear in federation slogans, resolutions and promotional materials.47

It is noteworthy that Greenberg’s approach to tikkun olam embedded the universal value within a particularistic mode of expression. For example, Greenberg taught that the weekly celebration of Shabbat, a profoundly particularistic rite that distinguishes Israel from other nations, also serves as a weekly reminder of the vision of a world redeemed. “The Shabbat prohibitions aim to create a messianic ambience. Work (tikkun olam) stops when the world is made perfect.”48 Similarly, he believed that the Jewish state was the ideal environment in which the Jews could practice tikkun olam. Political power constituted a challenge within an opportunity. Israel will be judged by how it makes its values manifest in its social, economic and defense policy.49

Although Greenberg wielded considerable influence, he was not the only one who used the language of covenant and tikkun olam in describing the role of federations and their constituent agencies. In 1978, political scientist Daniel Elazar argued that the system of Jewish federations was a continuation of the historical examples of Jewish communal government. He thus identified an enduring Jewish political tradition based upon “the biblical idea of covenant and the political principles that flow from it.” While Jewish governments over time differed in their structure and form, all of them affirmed “God’s kingship over Israel and the partnership between God and Israel in tikkun olam (improvement of society, literally repair the universe).” According to Elazar, the federations constituted an American adaptation of the covenant principle. Hence, unabashedly secular Jews appeared to be committed to creating “a covenant relationship with their tradition” even as they denied or marginalized God.50

Three years later, in a study of the attitudes and values of Jewish communal leaders, published in the American Jewish Year Book, Jonathan Woocher identified tikkun olam as a central tenet of American Jewish civil religion. The article anticipated his major study of American Jewish civil religion (a category introduced to the sociology of American religion by Robert Bellah) in which Woocher traced the evolution of civil Judaism from a basic “mobilization” or a survivalist model to a covenant model. He identified tikkun olam as the essential work of the Jewish people. “Only by viewing themselves as the people of the Covenant, as the effectors of tikkun olam, can contemporary Jews make sense of their determination to survive.”51 Neither Elazar nor Woocher were ivory tower academics. Despite the fact that they were not as influential as Greenberg, both frequently spoke at federation gatherings, engaged in Jewish public discourse and their works were widely read and respected by communal leaders.

TIKKUN OLAM: A PATH TOWARD RELEVANCE IN JEWISH EDUCATION

In addition to public intellectuals such as Schulweis and Greenberg who helped bring tikkun olam into American Jewish discourse through communal professionals, Jewish education became an important conduit for its dissemination. We have noted that, in the 1940s, Alexander Dushkin had identified tikkun olam as a core Jewish value and thus introduced its contemporary meaning to hundreds of educators.

Perhaps, Shlomo Bardin was among those educators or he picked up the term during his stay in Mandate Palestine. The founder of the Brandeis Camp Institute,52 located since 1947 in Simi Valley, California, Bardin certainly played an important role in reintroducing tikkun olam. Jewish day school leader Bruce Powell vividly recalls his first encounter with Bardin in 1960, where he explained to a group of campers that “the purpose of Judaism” could be found in four words of the second paragraph of the Aleinu prayer: l’takeyn olam b’malkhut Shaddai. Bardin insisted that it was their “task” as Jews to “fix the world.” Powell was profoundly moved and compared it with President John F. Kennedy’s call to service in his first inaugural address, delivered in January 1961.

As a young person at the time, believe me, it was a bolt of lightning and transformation for the thousands of Camp Alonimers and BCIers who heard it over time. When Bardin spoke of tikkun olam, it fit the times and minds of those who heard him. For some of us, it created an entire life path.53

The election of a youthful-looking Catholic president offered a message of idealism and optimism and seemed to promise a more inclusive America. According to one observer, “the restless spirits among Jewish college youth who, only a few years ago had been critical of the affluent society, find in the utterances of Kennedy and his co-workers ideas that are dynamic and stimulating.” Educators like Bardin, whose social justice message reflected the zeitgeist, were able to exploit the idealism and channel the idealism and frame the impulse to service in Jewish terms.

Their accomplishment was reflected in the complaint of Judah Pilch, director of the National Curriculum Research Institute of the American Association for Jewish Education, who remarked in 1962 that the success of Jewish educators in imbuing students with a sense of “tikkun haolam” was thwarting efforts to encourage aliyah. For Pilch, the Kennedy-era idealism that made young people like Bruce Powell receptive to Bardin’s message was a formidable challenge for any Zionist educator. The universal redemption embodied in tikkun haolam—“striv[ing] for the betterment of the lot of mankind”—according to Pilch’s translation—had to be balanced by the Jewishly focused concept of geulah (religious-national redemption).54

Pilch’s diagnosis notwithstanding, aliyah from North America was relatively stagnant between 1948 and 1967, and even rose modestly between 1962 and 1964.55 Nevertheless, Pilch predicted that the apparent consonance between Jewish values and Kennedy’s brand of democratic liberalism would convince Jews that “we in America can have Jewish self-fulfillment in furthering American idealism.”56 Others, however, would wonder whether the strong identification of Judaism and liberalism would leave American Jews without a compelling rationale for retaining a distinctive Jewish identity.

Tikkun olam remained a fairly obscure term throughout the early 1960s, regardless of the resonance of prophetic Judaism and social action. Although young people in educational settings such as the Brandeis Camp Institute and their parents who attended synagogues such as Schulweis’ Temple Beth Abraham were exposed to tikkun olam, it did not enter their Jewish vocabularies. A gradual change took place in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Fearing trends of rebellion and apathy among the youth, several educators, led by the American Association for Jewish Education, argued that the religious school curriculum urgently required reforms. The demand for more “relevance” in the curriculum joined a call for renewed emphasis on the teaching of Jewish values.

Similarly, in a message to many general educators in 1968, Zalmen Slesinger, editor of the AAJE’s quarterly magazine, The Pedagogic Reporter, declared that the rebellion of young people was “symptomatic of an ailing society and a culture in disarray.” He blamed the seemingly high Jewish “cultural dropout” rate among youth on

…a community whose spiritual heritage has become, more or less, frozen into outdated patterns of thought and content; whose dominating value system appears neither relevant nor responsive to the demands of the emerging world; whose institutions seem to resist the basic adjustments geared to liquidate needless deprivations of social improvement and self fulfillment…and whose leadership is too often visionless, socially myopic and at times, even self seeking. 57

Slesinger attributed the “ethical lag” in Jewish education to “social complacency” among the suburbanized World War II generation. There was a “crying need for education for social change and social improvement,” as well as cultural continuity.

In a separate article, Slesinger advocated the introduction of values education in the Jewish schools, with the point of departure—the “social issues and problems of the day.” Creating virtuous and ethical individuals was not enough. The teaching of Jewish values had to imbue young people with the imperative to build an “ethical social order.” He argued that Jewish youth should participate in “ethical experiences” through social action programs. Perhaps Slesinger’s most controversial statement was his call for the elimination of “all aspects of ethnocentricity in our ethical teachings. In a free, open and interdependent society, ethical teaching must be set in universal rather than ethnocentric terms.”58

His concerns appeared in a report by the United Synagogue Commission on Jewish Education of the Conservative movement in 1969. Issued by a committee convened in order to discuss responses to the “urban crisis,” the report criticized educators for not approaching the teaching of social justice in “sufficiently creative ways.” It recommended the enhancement of curricula devoted to “Tikkun olam, Mishpat [justice], and the like,” and the explicit linkage of these value concepts to explorations of contemporary Black-Jewish relations. “The approach should be to sensitize the students to the traditional emphasis on social justice, on the one hand, along with a realistic appraisal of the sociological tensions which obtain, on the other…”59

Rabbi Raphael Artz, director of Camp Ramah in New England, also advocated a values-oriented approach to Jewish education for teenagers. In an address to the 1967 Educators Assembly of United Synagogue, Arzt proclaimed that the “major problem in Jewish education today…is how to create from a sociologically constituted community of youth a value-culture,” where Jewish young people would seek to “concretize Jewish values in a meaningful way in contemporary culture.” Arzt included tikkun olam, which he translated as “correction of the world,” among a list of “fundamental values” that tended toward the universal.

“The ultimate goal of man’s partnership with God is Tikkun olam,” he argued. “The realization of a state of universal kedushah [holiness] will signal the full state of Tikkun olam.” He encouraged the inculcation of tikkun olam through the study of classical Jewish texts that “reflect the Utopian thrust of Judaism,” as well as an exploration of contemporary social movements, such as the kibbutz movement, that embodied “the universal aspects of Jewish tradition.” Unlike Slesinger, Arzt believed that universalistic Jewish “fundamental values” could be expressed in the more particularistic “symbolic” values, like the Sabbath and kashrut.60

As Arzt and others were working to emphasize values in the camp setting, Conservative educators also made efforts to reach a greater number of young people through the movement’s youth group, United Synagogue Youth. Established in 1950 by Morton Siegel, USY tried to appeal to teenagers who were not likely to participate in organized Jewish activities. According to its platform, the philosophy of USY was “learning by living Jewishly.” At first, the programs were mainly social and recreational. Criticism from youth leaders, Jewish Theological Seminary Teachers Institute officials, and others in the Conservative movement prompted efforts to strengthen USY programming in the areas of Jewish culture, social action and worship.61 In 1970, determined to place greater emphasis on tzedakah and social justice, USY leaders revamped and expanded its Building Spiritual Bridges program and renamed it Tikun Olam. All of its social action and tzedakah programs were coordinated through this project, and, in 1975, an accompanying educational guide was published with the same title.62

The call for increased attention to teaching values as part of Jewish education coincided with a general revival of interest in moral and character education in American schools. Prompted in part by the youth rebellion and the perception of social crisis in the mid-late 1960s, the movement derived momentum from the emergence of new approaches to moral education, most notably values clarification (developed by Louis Raths, Merrill Hermin and Sydney B. Simon in Values and Teaching (1966)) and the study of cognitive development, elaborated in the work of Harvard psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg. Kohlberg’s ties to Israel (he joined the Haganah, smuggled Holocaust survivors into Palestine, and later spent time on a kibbutz) may have helped stimulate interest in his theories among Jewish educators.

In the late 1960s, however, the values clarification model of Raths and his colleagues attracted great attention. Their method encouraged teachers to use non-judgmental exercises and activities in order to facilitate the discovery and application of values on the part of their students. Its lack of didacticism and promotion of autonomy appealed to progressive Jewish educators such as Slesinger. More traditional Jewish educators, however, maintained that its open-ended approach promoted relativism and undermined cultural and religious continuity.63

By the 1980s, the journey of tikkun olam into the Jewish educational mainstream was complete when it was promoted as a major Jewish value for religious school curricula by a younger generation of educators active in the Coalition for Alternatives in Jewish Education (CAJE). CAJE emerged in 1976 as the brainchild of activists who had been involved in the late 1960s Jewish counterculture and the havurah movement. Its annual conference, which drew hundreds of teachers and other educators, was hailed by textbook author Seymour Rossel as “the Jewish Woodstock.” In the early years of CAJE, largely due to the influence of educator-activist Danny Siegel, the main Hebrew word for social action was tzedakah. In fact, tzedakah was the subject of CAJE’s first special curriculum, published in 1981. By the mid-late 1980s, an increasing number of curricular materials published by the CAJE Curriculum Bank in its publication, Bikurim, were devoted to teaching tikkun olam.

The subject matter presented in these curricula was eclectic, ranging from nuclear proliferation to sanctuary for illegal immigrants. Likewise, the extent to which the curricula incorporated Jewish texts and concepts, and Hebrew words, varied considerably. One program, a “Tikkun Olam board game,” included game cards with directions like, “People have the ability to make powerful chemicals. Those chemicals, when used carelessly, can poison groundwater and destroy wildlife and their habitat. Move back two spaces”; and “We are taught to remember that we were slaves in Egypt. Today people work hard so that the Jewish communities of Russia and Ethiopia will be redeemed. Move ahead three spaces. If you will have a Bar/Bat Mitzvah ‘twin’ or have written to an ‘adopted’ Refusenik family, move ahead another two spaces.”

Another CAJE curriculum encouraged students to keep a journal and asked them to respond to questions such as, “In doing tikkun olam, do you feel there is a difference between giving money and giving of yourself?” and “Can you name some people today who are fixers? How have these fixers changed their worlds?”64

In the 1980s, tikkun olam also began to appear in the curricula of the Reform movement. As in the Conservative movement, the discussion of tikkun olam often occurred within the context of values and character education or was linked to social action and social justice programming. For example, a curriculum on AIDS education entitled Nechama, included tikkun olam among a number of “mitzvot” that it stressed, including bikur holim (visiting the sick), pikuah nefesh (saving a life), and shituf betsa’ar (empathy). Originally created by the Los Angeles Gay and Lesbian Synagogue, Congregation Beth Chayim Chadashim, and disseminated by the Union of American Hebrew Congregations, the curriculum guide presented a simplified but fair summary of the kabbalistic interpretation of tikkun olam, and concluded with its application to the AIDS epidemic. Students were encouraged to provide financial support for medical research, initiate AIDS education programs in their communities, advocate for the rights of AIDS victims in the political arena, visit the sick and create support groups and “specially sensitized minyan[im] [worship services]” for families mourning loved ones who had succumbed to the disease.65

TIKKUN OLAM AS A POLITICAL CRI DE COEUR

Like many who incorporated tikkun olam into their vocabularies in the early and mid-1970s, Rabbi Gerald Serotta does not remember precisely where or from whom he first heard the term. As a member of the New York Havurah, it is possible that he picked it up there. The term also appeared in the pages of Response, an organ of the Jewish counterculture, to which Serotta was a regular subscriber. Or, he may have come across tikkun olam in a piece by anti-establishment activist and writer, Arthur Waskow entitled “How to Bring Mashiah.” The latter was one of the most popular and often reprinted sections in the widely read Jewish Catalog.

Many in the havurah movement grew up as Conservative Jews and most likely were first exposed to tikkun olam at Camp Ramah or through USY. Former USY president, the founding editor of Response and an early member of the New York havurah, Alan Mintz agreed that tikkun olam was used “extensively” in programs for Conservative Jewish youth in the late 1960s and early 1970s.66 Another early advocate of tikkun olam was Everett Gendler, a JTS-trained Hillel rabbi at Princeton University. Many students at JTS and others were inspired by the example of faculty member Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. While Heschel himself apparently never used the term tikkun olam in his published writings, his activism was regarded as the embodiment of the social justice ethos.67 Champions of tikkun olam liked to invoke Heschel’s statement in a letter to Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. after the civil rights march to Selma, Alabama in 1965: “Legs are not lips and walking is not kneeling. And yet our legs uttered songs. Even without words our march was worship. I felt my legs were praying.”68 After his death in December 1972, friends, students and admirers, including Rabbis Balfour Brickner and Michael Lerner, did not hesitate to describe Heschel’s activism as tikkun olam.69

An article in The Jewish Catalog, however, was most important in spreading the idea of tikkun olam throughout North America. According to historian Jonathan Sarna, “few books in all of American Jewish history have ever been as influential.” Modeled after The Whole Earth Catalogue, the book was the brainchild of two Brandeis University graduate students, George Savran and Richard Siegel. Attracted by the “do-it-yourself” ethos of The Whole Earth Catalogue, its editorial team of Siegel, Sharon Strassfeld and Michael Strassfeld aimed at creating a “compendium of tools and resources” for the Jewish counterculture. It eventually became part catalog and part “guide or manual to the range of contemporary Jewish life.” An overwhelming success, it sold over 130,000 copies in eighteen months, and remained extremely popular afterward. According to its publisher, the Jewish Publication Society, only its translation of the Hebrew Bible sold more copies on an annual basis. Two sequels were published, and the book inspired numerous imitators.

According to Sarna, the three volumes of the Jewish Catalog were the most enduring legacy of the Jewish counterculture. They “served as a vehicle for transmitting the innovations pioneered by pockets of creative students, chiefly in Boston and New York, to Jews throughout North America, and beyond.” These included the language of the havurah movement, including words like tzedakah, kavanah (intentionality) and tikkun olam.70

Arthur Waskow urged readers to “plant a tree somewhere as a small tikkun olam—fixing up the world—wherever the olam most needs it,” in his commentary on the passage in Avot d’Rabbi Nathan B31, where rabbinic sage Johanan ben Zakkai taught that if one is in the midst of planting a sapling and hears that the Messiah has come, one should finish planting before going to welcome the Messiah at the city gates.

Plant a tree in Vietnam in a defoliated former forest… Plant a tree in Appalachia where the strip mines have poisoned the forests. Go there to plant it; start a kibbutz there and grow more trees. Plant a tree in Brooklyn where the asphalt has buried the forest. Go back there to plant it and live with some of the old Jews who still live there.71

Waskow overtly politicized and expanded the meaning of tikkun olam to include a variety of causes, both universal and particular, from environmentalism and anti-Vietnam War activism to caring for the Jewish elderly and neighborhood gentrification (ostensibly to make formerly Jewish areas safer and more livable for those who remained there).

Waskow remembers that he was “totally tickled by the idea of treating bringing Mashiah (the Messiah) as a ‘how-to-do-it’ project.” He probably learned about tikkun olam from Rabbi Max Ticktin and Robert Agus at Farbrengen, the Washington, DC havurah. “We really thought that we were borrowing an obscure Kabbalistic idiom,” recalled Ticktin, a Hebrew linguist who, like Gendler, spent his early career as a Hillel director. (Ticktin was also aware that the term had been used for many decades “in Zionist circles.”) Agus concurred, noting that social justice was integral to Farbrengen’s mission, along with study, prayer, Jewish cultural expression and environmentalism. He recalled:

I felt the Kabbalistic use of kavannot as a force to make a better world – a time, a place and community brought together momentarily and then eternally through the focus on kedushah was a goal and a teaching we should pursue. I was afraid that we might confuse our search for the Eternal truth and insight with our own limited understandings…. Though not perfect, the ideal of the coming together of kavanah and tikkun was worthwhile and a valuable channel for great thoughts and commitments. In my view, tikkun olam is a goal not an end.72

According to Waskow, it was Serotta who became a “flag-bearer for the phrase.” In 1975, a year after his ordination by Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, Serotta became interested in the derivation and meaning of the idiom. Eager to find a term that could express what he believed were the core Jewish values that infused social justice activism, Serotta approached one of his teachers, Eugene Borowitz, about tracing the application of tikkun olam in rabbinic literature.73 He was surprised to learn that the majority of cases where tikkun olam was mentioned were associated with divorce law. This led Borowitz to suggest that he would find another rabbinic idiom, “mipnei darkhei shalom,” for the sake of social peace, more useful for his purposes. Serotta, however, was intrigued by the Talmudic passages in which tikkun olam was associated with economic justice. While he acknowledged that the term in Talmudic literature clearly referred only to Jews, his prayer experiences at New York havurah retreats exposed him to the more universalistic usage in the second paragraph of Aleinu. (Serotta grew up in a Reform family and worshipped from the Union Prayerbook, which did not include l’taken olam in its poetic rendering of the second paragraph.) Later, he also became familiar with the Lurianic vision of humanity and God working in partnership to perfect the world.74

Serotta’s growing interest in tikkun olam coincided with the collapse of the controversial Breira movement which was regarded by most American Jews as undermining support for Israel.75 An active member of Breira, Serotta assembled a group of former Breira members to bolster support for a new organization and eventually drafted the “New Jewish Manifesto,” a multi-issue progressive Jewish policy statement. Encouraged by the response, he organized a national meeting of progressive Jewish leaders in May 1979. The meeting led to the founding conference of the New Jewish Agenda in December 1980.76

The success of the founding conference, which attracted over 700 participants, was the result of intense publicity and recruitment on the part of Serotta and his colleagues. Serotta presented his vision for the New Jewish Agenda at the July 1979 National Havurah Conference and in politically liberal and centrist Jewish media outlets, ranging from the Jewish Spectator and the Jewish Frontier to Sh’ma and Moment magazine. There was considerable support for a platform that promoted policies that focused upon improving the quality of Diaspora Jewish life and many strongly identified with a draft statement that read, in part: “We are Jews who believe strongly that authentic Jewishness can only be complete with serious and consistent attention to Tikun Olam (the just ordering of human relationships and the physical-spiritual world).” Serotta further argued that “efforts to construct a new agenda for the 80s can be seen as a radical return to an understanding of Jewish wholeness which denies distinctions between Jewish and non-Jewish issues, and which seeks to bring Torah and Jewish learning to even greater application in the world.”77

Serotta’s statement and his definition of tikkun olam envisioned progressive politics informed and driven by Jewish teachings. Skeptics within his own camp, such as havurah member and journalist Charles Silberman, wondered aloud whether there was a clear-cut “Jewish position” on many of the contemporary political, economic and social issues that mobilized the Jewish Left. For example, the Hebrew Bible was unequivocal in its call for economic justice, but it did not overtly endorse any particular economic program. The Hebrew prophets were neither socialists nor laissez-faire capitalists. A sophisticated reader of classical Jewish texts, Serotta insisted that abstract Jewish values should guide the organization’s political commitments. For example, as far as abortion was concerned, he bypassed the complex responsa literature and its debates about various technical issues and focused upon the general principle of “lev yode’a marat nafsho—the heart knows its own bitterness,” in order to advocate for “a woman’s right to control her own body.” But he balanced this position with the Torah’s command to “be fruitful and multiply,” and the concerns about Jewish continuity in the wake of the Holocaust, as follows:

As the sum total of Agenda’s view of the reproductive freedom issue, the right of a woman to control her own body is an inadequate position. We have more to say about what our community should do to support women who choose to have children and thus assure Jewish survival. We must balance ethical issues with our personal concerns.78

Tikkun olam remained an important motif for the New Jewish Agenda throughout the 1980s, and was invoked in its founding documents, platform and policy statements. Its “Call for a 1980 Congress of Progressive Jews,” disseminated by the organizing committee, criticized what it termed as

the false dichotomy between Jewish issues and other concerns, between particularism and universalism. As Jews who believe strongly that authentic Jewishness can only be complete with serious and consistent attention to Tikun Olam (the just ordering of the physical world and human relationships), we believe it is time to join together…79

Likewise, a 1979 Statement of Purpose that was published on the nascent organization’s letterhead read:

We are Jews concerned with the retreat from social action concerns and open discussion within the Jewish community. As Jews who believe strongly that authentic Jewish life must involve serious and consistent attention to the just ordering of human society and the natural resources of our world (Tikun Olam), we seek to employ Jewish values to such questions as economic justice, ecological concerns, energy policy, world hunger, intergroup relations, and affirmative action, women’s rights, peace in the Middle East, and Jewish education.80

The Statement of Purpose was revised at the founding conference in December 1980, but the reference to tikkun olam was retained.81 Similarly, the opening section of the National Platform, adopted on November 28, 1982, declared that the organization looked to “history and traditions” and to “Jewish experience and teachings” to guide its approach to “the social, economic, and political issues of our time.” New Jewish Agenda members were inspired by “our people’s historical resistance to oppression,” and “the Jewish presence at the forefront of movements for social change.” The platform asserted that “many of us base our convictions on the Jewish religious concept of tikun olam (the just ordering of human society and the world) and the prophetic traditions of social justice.”82

Some may argue that Serotta and the New Jewish Agenda were instrumental in transforming tikkun olam into a Jewish fig leaf for an essentially secular, liberal agenda, based upon a selective use of passages from the biblical and rabbinic corpus. Serotta and the New Jewish Agenda may have been regarded as committing the original sin that spawned a thousand imitators. Indeed, he and his colleagues were selective in their choice of passages from the classical sources, and they undoubtedly read their own values into these texts. Their approach, however, was not unique. Over twenty percent of those who attended the organizing meeting of the New Jewish Agenda were rabbis, Jewish educators and communal workers,83 who interpreted texts in that manner.

Serotta’s allies within the havurah movement staunchly defended him. Michael and Sharon Strassfeld, editors of the Third Jewish Catalog, rejected the complaint that tikkun olam had become politicized and asserted that repairing the world by making it “more just, more whole” was an inherently political act that “can take place only through the interactions between people and between communities.” In a section on social action, Jonathan Wolf argued that Jewish teachings and law concerned itself as much with human interrelations, the social and political realm, as with the personal sphere and the relationship between humanity and the divine. Insisting that in the wake of the destruction of the Temple, the rabbis were not afraid to challenge the status quo, the Catalog portrayed them as social and political revolutionaries. Contemporary Jewry had “little choice” but to follow in their footsteps.84

Moreover, as director of the B’nai Brith Hillel Foundation at Rutgers University, Serotta was alarmed at “the tragically truncated Jewish identity” of his students. He blamed it on a vacuous postwar Judaism chiefly concerned with bourgeois materialism, personal accomplishment, survivalism and a narrow and ethnocentric political agenda that began and ended with security for Israel, memorializing the Holocaust and relief for oppressed Jewish communities throughout the world. A Judaism that did not confront the issues that dominated public discourse, such as nuclear proliferation, energy policy, women’s rights, and urban decay rendered itself irrelevant. Young Jews were dropping out of the Jewish community in droves or relegating Judaism to “an insignificant part of their lives.” Serotta warned that “for them Judaism is an artifact whose primary demand is negative—do not intermarry—rather than a positive command for perfecting the world. The message my students are receiving from the organized Jewish community threatens the survival of Jewish values.” He regarded the New Jewish Agenda and its emphasis on tikkun olam as a way of reengaging young people in Judaism through their activism. Thus, tikkun olam was to serve as a banner of Jewish revival rather than a rationalization for assimilation and a gateway to secular humanism.85

The New Jewish Agenda also may be understood as a response to the politicization of Protestant Evangelicals in the 1970s and the establishment of groups such as the Moral Majority. This movement emerged partially as a cultural backlash against the excesses of the social revolution of the 1960s. According to leading sociologist Robert Wuthnow, the rise of the New Christian Right as a political force coincided with a lowering of the unofficial barrier between private morality and public life. For Evangelicals, “faith and morals” were merely “two sides of the same coin.” Thus, in the minds of many Evangelicals it was natural to become politically active in order to uphold standards of morality and decency. The growth of the New Christian Right and its effort to define the terms of the debate by equating morality with conservative religious values placed religious liberals on the defensive and left them feeling as if they lacked a voice.86

Serotta noted that “the conservative shift in the American community has left an enormously large political group unrepresented.” Liberal religiously oriented political organizations, such as the New Jewish Agenda, were essential in order to counteract the influence of the religious right on the public discourse. By arguing that “the social action gospel is in serious need of a new theological underpinning which takes greater note of the values of Jewish particularism,” Serotta himself inadvertently reflected the influence of the religious right.87

THE MAINSTREAMING OF TIKKUN OLAM

When the New Jewish Agenda ultimately collapsed in 1992, others took up the effort to shape a progressive Jewish politics around tikkun olam. The most important figures were Leonard Fein and Michael Lerner. An activist and founding editor of Moment magazine, Fein preached a message that combined the views of Irving Greenberg and Gerry Serotta. Like Greenberg, his message was aimed at the Jewish mainstream, including the federations and Hadassah, as well as alumni of the Jewish counterculture. Fein’s lectures and his book, Where Are We? The Inner Life of American Jews (1988), argued that survivalism, either for its own sake or as a response to the Holocaust, was an instrumental value at best. He emphasized that the purpose of Jewish continuity must extend beyond the parochial interests of an ethnic group, no matter its venerable pedigree. He believed that “there is only one agenda that warrants the effort and that dignifies the pursuit, and that purpose is what it has always been, to enter into partnership with God in completing the work of creation.” Like Schulweis, Greenberg and others, Fein viewed tikkun olam as the ground “where particularism and universalism meet,” where Jews are afforded the opportunity to live their ethics and thereby “move from ethics to justice.”88

Fein tried to spread his message through the founding of AMOS: The National Partnership for Social Justice in 2001. While the organization closed in the wake of the post-9/11 recession, its mission to connect young unaffiliated Jews to their Judaism through social justice and service learning was continued by a growing number of more narrowly targeted organizations, such as AVODAH: The Jewish Service Corps, the Jewish Organizing Initiative and the American Jewish World Service. Fein also spread his message by working closely with the local federations, other communal service professionals and with the Nathan Cummings Foundation, which funded research and individual grants for service learning and synagogue-based community organizing initiatives.89

Fein strongly maintained that far from endangering Jewish survival by making Judaism indistinguishable from liberalism or secular humanism, tikkun olam gave purpose and meaning to Jewish survival. This argument, however, was not immune to criticism. Fein himself acknowledged that if one presented the rich and venerable Jewish tradition as a gateway to universal ideals, it no longer was indispensable and Judaism was no longer a desideratum. The road to world improvement could be accessed with equally satisfying results through a host of other traditions, philosophies and media. He told the story of a young woman who asked him why she should remain connected to her Jewish heritage despite her lack of interest in Jewish ritual. “I need to know why it should matter to me whether the Jewish people survives?” she asked him earnestly. When Fein responded by invoking “the vocation of the Jews… tikun olam,” she remained unmoved. She explained that she pursued tikkun olam through her feminist activism and her career as a composer of music. For her, Judaism as tikkun olam was superfluous at best. Fein reluctantly admitted that if the ultimate goal is tikkun olam, instrumentality is a matter of preference. For Fein himself, the connection to Judaism was almost instinctive, but it was not true for everyone.90

Likewise, others objected to tikkun olam Judaism because of the “poverty of its religious vision.” As Yehudah Mirsky argued, “by pushing the social and political dimensions of Jewish experience to the foreground,” the purveyors of tikkun olam Judaism “neglect[ed]—even violate[d]—much of the fabric and spirit of Judaism as lived through the ages.” To be fair, this tendency was more obvious in the vision of secular Jews like Fein than in the writings of observant Jews like Greenberg. Indeed, Greenberg joined tikkun olam with tikkun ha-adam, the repair of humanity, the mending of souls. Fein represented many Jews, particularly among the baby boomers and their elders, when he asserted: “Politics is our religion; liberalism is the preferred denomination.” But the narrowness of this vision, whether advocated by Fein or by champions of American Jewish civil religion, such as Woocher, excluded those seeking fulfillment through spiritual, religious, cultural or intellectual Jewish pursuits. The growing privatization of religion in recent decades only served to strengthen this critique.91

At the same time, academic, mental health professional and left-wing political activist Michael Lerner and his wife (at that time), drug store chain heiress and psychotherapist Nan Fink took up the cause of tikkun olam. They co-founded TIKKUN, a political and cultural journal that was intended as a left-wing alternative to the neo-conservative Commentary magazine. Each issue carried a definition of “tikkun (tē · kün)” on its cover: “To mend, repair and transform the world.” In several respects, Lerner’s goals for TIKKUN, as expressed in his “Founding Editorial Statement” resembled those of Serotta. Like the founders of Agenda, Lerner expressed his frustration with the complacency of the American Jewish establishment. “The notion that the world could and should be different than it is…seems strangely out of fashion,” he complained in his opening paragraph. Insisting that the Jewish commitment to liberal politics was based on deeply rooted Jewish values, and not merely on perceived political interest, Lerner hoped that TIKKUN would help keep “the Prophetic tradition alive.”

He defined Judaism as a religion that was “irrevocably committed to the side of the oppressed” and the biblical accounts of Creation and the Exodus as infused with the message that “the world needs to be and can be transformed, that history is not meaningless but aimed at liberation…” According to Lerner, this essential teaching led inexorably to a progressive political and social agenda. Lerner was careful not to over-glorify the Left and criticized its tendency to “force Jews into a false universalism,” turn a blind eye to anti-Semitism in its midst, and “apply a double standard towards Israel.” Like Serotta, he also hoped that by embedding a dovish critique of Israeli policies vis-à-vis the Palestinians into the magazine’s larger American Jewish political program, it would not end the same way as the Breira movement.92